According to legends, the Aztecs came from Aztlan and migrated to what is now known as Mexico around the 13th century. They built their city, Tenochtitlan, following the directions of Huitzilopochtli, their patron god. The god said the city should be in a location where a giant eagle was eating a snake while resting on a cactus. From the beginning, the Aztecs were already using animal symbolism. As an agricultural group, the massive 25-ton Aztec calendar, discovered in 1790, showed how the Aztecs used symbols to depict different times of the day, deities, months, and seasons. The Calendar or Sun Stone contains a sacred 260-day tōnalpōhualli and a 365-day xiuhpōhualli solar calendar, with the two representing the rich symbols of their culture. They described their daily activities through animalistic symbols. But in using symbols, the Aztecs used the attributes of animals to describe humans.

Monkey

The Monkey or Ozomahtli symbol was associated with the god Xochipili or the Flower Prince. Xochipili was the god of fun, creativity, feasts, and flowers. It represented a frivolous and light-hearted day. The monkey day was for creating, celebrating, and playing. It was also a day for lightheartedness where people should not be serious. The monkey also symbolized how the lures of public life could easily trap even a noble person. Patecatl ruled the monkey day.

The trecena was devoted to finding cures for various ailments and searching for power that can overcome the misfortunes that lie within a warrior’s intention, such as turning poison into medicine or evil into good, which could make a difference during battle. Aztecs used the day to collect ingredients for medicines.

Dog

The Dog (Itzcuintli) was the 10th day in the Aztec calendar. In ancient times, they buried the dog along with the dead. The dog was a guide to the afterlife because the Aztecs believed that the animal could help the dead cross the underworld’s nine-fold river.

The deity Itzcuintli represented an auspicious day for wakes, funerals, and remembering the departed. It was also a good day to be trustworthy but a lousy day for trusting others who have questionable intentions. Xipe Totec, the god of seedtime and the Lord of Shedding, ruled the day. The period was for devotion, self-sacrifice, love, and companionship. It was characterized by the eternal conflicts humans face—mysticism and love and the struggle to survive being swallowed by one or the other. The day was also about the pleasure of creating an illusion and shedding illusions.

Itzcuintli represented Mictlantecuhtli, the god of death, who also ruled the lowest underworld.

Flower

Xochitl or the Flower symbol was governed by the Flower Feather or Xochiquetzal, the goddess of beauty, pleasure, love, and youth. The day was for creating truth and beauty. It concerned speaking to someone who knows that the heart will someday stop beating. The Xochitl served as a reminder that life was like a flower that could be beautiful to look at, but fades quickly. The day was good for poignancy, companionship, and reflection. It was not a day for repressing passions, desires, and deep-seated wants.

The trecena starting with Xochitl was ruled by Huehuecoyotl, also called the god of deception, the Trickster, or the Old Coyote. The day stood for the sacred role of the jester in revealing the truth of the old ways, which they treated irreverently. The trecena was influenced by playfulness and creativity to peel off the layers of masks people wore.

Rain

The Rain (Quiahuitl) symbol was regulated by Tonatiuh, the sun god. The day represented the unpredictable fortunes laid out by fate. It was a good day for learning and traveling, but a bad day for planning and business.

The day of Quiahuitl was under Tlaloc’s rule or the god of thunder, lightning and rain, and the one who makes things sprout. The trecena represented the time where flood and drought alternated. There was either too much or too little; a time of suffering and hardship. There could be people who prepared for disaster, but not enough for everyone who needed help.

Stone Knife

The Stone Knife (Tecpatl) symbol’s governing deity was Chalchihuihtotolin or the Jeweled Fowl, the god of disaster and plagues. He symbolized powerful sorcery. He could shift shape into animal forms. The Tecpatl day was a time of trials and tribulations and a day of ordeals. It was a good day for testing one’s character and a bad day to rely on past reputation or accomplishments. The Aztecs believed that Tecpatl warned them that they should sharpen their spirit and the mind like the glass blade that cuts to the core of the truth.

The god of death, Mictlantecuhtli, ruled the Stone Knife. The trecena signified the trial or ordeal that pushed one to the verge of endurance. Likewise, the symbol foretold a sudden change in the continuity of things.

Movement

The symbol Ollin translates to Movement, Motion, or Quake. The primary presentation of the symbol showed two interlaced lines, with each line portrayed with two central ends. The concept alluded to the ages in history or the four preceding suns. The Aztecs believed that Ollin was a representation of the fifth sun. Their legend said that Quetzalcoatl traveled to the underworld (Mictlān) to collect bones from the past age and initiated a process of human re-birth. Moreover, according to Aztec belief, the fifth world will also be destroyed by a series of disastrous earthquakes or one large earthquake that will result in a period of darkness and famine.

Ollin, was a day associated with Xiloti, the god of shifting shapes, Venus (the Evening Star), and the twins. The symbol represented seismic change, disorder, and transmutation. It was a bad day to be passive, but a good day for active people.

Vulture

Itzpapalotl ruled the Vulture (Cozcacuauhtli) day. The vulture symbol signified long life, mental equilibrium, good counsel, and wisdom. It was a good day to confront deaths, failures, disruptions, and discontinuities. Xoloti ruled the trecena (13-day period) that started with the vulture. It was a period focused on the freedom and wisdom of old age, representing the setting sun. While the younger generation strategizes between defense and offense, the older generation only takes things other people do not want. The day was considered a good day for disengagement.

In the Aztec calendar, Itzpapaloti was the goddess of purification, sacrifice, and rejuvenation. She was also referred to as the Obsidian Butterfly and was a representation of a good day for facing challenges head-on and overcoming deceitful people.

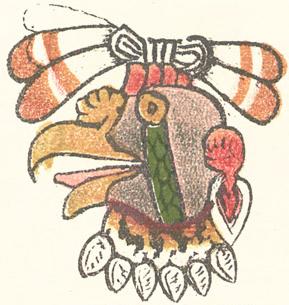

Eagle

The Eagle (Quauhtli), representing the 15th day in the Aztec calendar, symbolized power and warlike qualities. It described the largest bird—a powerful, brave, and fearless bird—just like the warriors it represented. In the Aztec Empire, the eagle symbolized another elite warrior group, the Eagle Warriors, which dedicated themselves to the sun. They were the second well-known warrior caste in the empire.

The representation of the eagle’s flight was the sun’s journey from night to day. Likewise, the bird was also related to stealing and plundering in the military context.

The ancient tribe included the eagle in the emblem of Tenochtitlan, the Aztec capital because the Aztecs believed they were descendants of the nomadic Mexica people who traveled around Mesoamerica to search for their new home. As the eagle symbolized the incarnation of the revered god Huitzilopochtli, the land where they eventually settled was a swampy island where an eagle was resting on a cactus. The regard of the Aztecs for the eagle was so high that it became a part of the national flag of Mexico.

The symbol of the eagle represented the day related to Xipe Totec, the goddess of skin shedding, rebirth, and seeds. The goddess symbolized transformation, the spring season, and the day for equality and freedom.

Jaguar

The Jaguar (Ocelotl) symbolized the Jaguar Warriors, the Aztecs’ elite warriors. The animal is the largest wild feline cat and alpha predator. It was a symbol of power for the Aztec military that included only the most battle-hardened and skilled warriors.

The Ocelotl warriors had the privilege to wear the Ocelotl warrior costume symbolizing the jaguar. They believed that they had the protection and power of the largest beast of prey.

In the Aztec culture, the jaguar represented a cult and shamanic animal related to offerings and ceremonies to the jaguar god, Tezcatlipoca. He was depicted as a jaguar with an eagle by his side. The Aztec Emperor’s status symbols, the jaguar skin and eagle feathers, adorned Tezcatlipoca’s throne.

On the Aztec calendar, the jaguar symbolized the 14th day of the 20 day-signs. The day was related to Tlazōlteōtl, the god of vice, lust, filth, and purification.

Reed

Tezcatlipoca governed the Reed symbol (Acatl). The symbol was the scepter of authority, although it was hollow. It was associated with a day to seek justice but not to act against other people. Chalchihuitlicue, the goddess of seas, rivers, lakes, and horizontal waters ruled the reed day.

The trecena period signified the transitory nature of everything people gained in life. It was a time for reviewing loss and gain, failures and successes, and relating them to the matter of fate rather than personal worth. The period was a time for reflection and deciding whether the person wanted to live in the house of shadows or find the secret of happiness somewhere else. The reed period was good for traveling to new places.

The symbol for reed was also associated with Tezcatlipoca, the god of providence. But the deity had several concepts associated with him, including conflict, war, beauty, sorcery, divination, rulership, the earth, hurricanes, night winds, hostility, and temptation. In some translations, he was also associated with the symbol, Ocelotl, or the jaguar.

Grass

The Grass (Malinalli) symbol signified rejuvenation, tenacity, and something that you cannot easily uproot. It was a day of perseverance, overcoming odds, and creating strong alliances.

The grass day was ruled by Mayahuel, the Aztec Goddes of the Maguey and Pulque. It was associated with passion, excitement, infatuation, and intoxication. It was a time of excesses, which often led to disaster. It became associated with the times when people cannot protect themselves from higher emotions when affairs of the heart and matters of war can suddenly occur. Moreover, it was associated with confusion, where only the most disciplined of warriors could control their emotions.

Water

The Aztec symbol for Water, or Atl, was governed by the god of fire, Xiuhtecuhtli, the deity of warmth and sustenance, creation, and personification of life. It was a day for purification where the person had to undergo conflict. It was a day of the holy war, which means battling one’s demons. It also characterized the emergence of the scorpion, which had the instinct to sting its enemies.

Its trecena was ruled by the deity Chalchihuihtotolin, the Jeweled Fowl, a symbol of powerful sorcery, a companion to the god Tezcatlipoca. The god, also called the Smoking Mirror, can tempt people into self-destruction. However, when he takes on the colorful turkey form, he can overcome the fate of people, free them from their guilt, and cleanse them of their sins. He personified change through conflict. Thus, the period was full of unexpected events, coincidences, and accidents. It was also a period when people should mimic water’s nature and become an agent of change.

Rabbit

The Rabbit symbol (Tochtli) was governed by the goddess of Maguey and Fertility, Mayahuel. The Rabbit day was for self-sacrifice. It denoted the religious attitude of holding everything sacred, which could lead to experiences of rising above oneself. As the day was associated with the moon’s passing, it was a good day for communing with the spirit and nature. For the Aztecs, the rabbit symbolized parties, drinking, and fertility.

The Rabbit trecena was ruled by Xiuhtecuhtli, the lord of the year. Tochtli was the last trecena of the sacred year in the Aztec calendar. Thus, it represented the end of a cycle and the beginning of another one. Therefore, it was a period that the Aztecs used to unite their goals. But it could represent dangerous times because the period was in the middle of a transition.

Deer

The day of the Deer (Mazatl) was governed by the god of rain and thunderstorms, Tlaloc. He was associated with wrath, droughts, floods, and fertility. It was a day for hunting and stalking whoever or whatever was a person’s quarry. Aztecs spent a Deer day breaking old routines, reviewing old actions, and paying close attention to other people’s actions.

Tepeyollotl, the Jaguar of Night, or the Heart of the Mountain, exerted influence within its trecena. The deity was also called the lord of darkened caves and animals. The deity was Tezcatlipoca, wearing a jaguar disguise. According to the legend, the god’s voice was the echo of the wilderness. The trecena was a reminder that the act of stalking determined the lives of humans, from tracking and backtracking to spotting and camouflaging, and following tracks and covering them.

Death

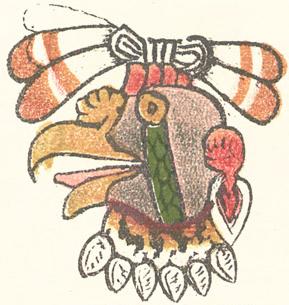

The Aztec symbol Miquiztli or Death was under the rule of the moon god, Tecciztecatl. It meant spending the day reflecting on one’s priorities and taking advantage of opportunities. It was also a day of transformation, showing that the old endings and new beginnings only had the briefest of gaps.

Tonatiuh, the sun god, or the current or Fifth World symbol, ruled the trecena. The period focused on the cosmological forces that influenced humans’ lives. The powers of the unknown determined the period. The events would pass by unnoticed unless something big occurred. Aztecs spent the days fulfilling previous obligations and promises.

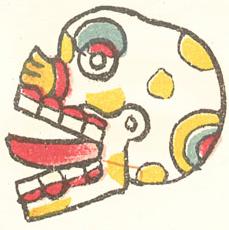

Snake

The Snake or Coatl was under the rule of the Chalchihuitlicue, the goddess of running water, rivers, and oceans. She was also related to labor and childbirth. The Snake day resembled a snaking river that constantly changes, although the river itself did not change. The day was a time to stay humble and selfless.

In its trecena, Xiuhtecuhtli rules the first day. The deity was the ancient god of fire. The 13 days of this period were led by opposing forces that created a vacuum. There was no one on the throne, and the rightful successor must fight all the claimants to the throne. Unexpected developments, intrigues, and conflicts marked this period. The throne will be in the hands of one who was able to lay the groundwork and build strong alliances. As with other rulers, those who have not completed their preparations should wait for the right time, while those holding the seats of power should remain vigilant.

Lizard

The Lizard (Cuetzpalin) symbolized quick reversals of fortune. The Trickster, Huehuecoyotl, governed the symbol. He was the god of cruel pranks and reversals but was also associated with dancing, music, and storytelling. It is good to work on one’s reputation not by words but through actions on a Lizard day.

Itzlacoliuhqui ruled the trecena that started with Cuetzplain, depicted as a period of confusion. It was a period where the nobles and the untitled had an equal chance to be honored or dishonored, rewarded or punished. A warrior must emulate the lizard, which cannot be hurt even if it falls from a high place. The day was good for keeping out of sight and not attracting attention.

House

The House symbol (Calli), according to the Aztecs, was not a good day for participating in public activities. The day should be spent forging relationships and mutual interests. Itzpapalotl ruled the day, governed by the conflict between nature and culture. Calli, the first of a 13-day group (trecena) in the Aztec calendar, spanned a time of struggle to decide which one they should call home—the one they were born in (nature) or the house they would move into (culture). The period was good for focusing on the future.

The symbol represented Tepeyolloti, the deity of earthquakes, echoes, caves, and animals. The Aztecs linked the Calli day to family, tranquility, and resting at home.

Wind

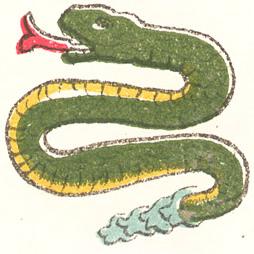

The Wind symbol (Ehecatl) was usually interpreted as a feature of the Feathered Serpent. The wind was one of the creator gods. Because the wind blows in all directions, the symbol was associated with the cardinal directions.

This symbol was associated with Quetzalcoatl, the aboriginal creator and the god of self-reflection and intelligence. The Aztecs relate the day to vanity and inconsistency. The Aztecs believed they should spend the day renouncing bad habits. It was also a day to work alone.

Crocodile

The Crocodile (Cipactli) was considered the first diviner by the Aztecs. It symbolized the Earth floating in the aboriginal waters. According to the Aztec tradition, they associated the term with the name of a flood survivor, Teocipactli, who rescued himself using a canoe. He supposedly started the Earth’s repopulation. According to the Mixtec Vienna Codex, the day of the crocodile represents a dynasty’s beginnings.

According to Aztec mythology, Cipactli was a sea monster that was part fish, part frog, and part crocodilian, with a mouth in every joint of its body because it was always hungry.

The crocodile symbol was associated with honor, advancement, recognition, and reward. It represented Tonacatecuhtli, another aboriginal creator and the god of new beginnings and fertility.