The Aztecs were polytheistic, and they worshiped more than 200 gods and goddesses that oversaw every part of their daily lives. They believed these deities controlled the various aspects of the universe, such as wars, fertility, agriculture, and weather.

They had four primary gods: Huitzilopochtli, Quetzalcoatl, Xipe Totec, and Tezcatlipoca, who were children of their original creator, Ometecuhtli.

The Aztecs believed that the sun was vital and the five stages of the world needed a sun. They likewise believed in the afterlife, and felt they were supposed to take care of the gods.

Building prominent temples was one way to worship their gods. However, two of the most common worship rituals they practiced were performing human sacrifices and cannibalism, which they believed they needed to do to please their gods and maintain order in their universe.

Here are 14 of the most prominent gods and goddesses the Aztecs worshipped.

Huitzilopochtli

Huitzilopochtli, regarded as the father of the Aztecs and Mexica’s supreme god, was uniquely a Mexica deity, with no equivalent deities in earlier cultures in Mesoamerica. The eagle was his spirit animal. He was the Aztecs’ god of the sun, war, and sacrifice, and his shrine was on top of the Templo Mayor pyramid in Tenochtitlán, which the Aztecs painted red for blood. They added skulls for decoration, as his people believed that the spirits of fallen warriors who returned to earth as hummingbirds accompanied him. Thus, he was also called the Hummingbird of the Left.

According to myth, Huitzilopochtli was the god who told the Aztecs where to settle when they moved from Aztlan to present-day Central Mexico. However, since he did not have any equivalent deity in the past, some scholars believed that he was probably a priest who, after death, transformed into a god.

Tezcatlipoca

One of the rivals of Huitzilopochtli was Tezcatlipoca, the god of the night sky, time, and ancestral memory. The jaguar was his animal (nagual) or guardian spirit. The Aztecs believed that these important gods, Huitzilopochtli and Tezcatlipoca, created the world, although the latter represented evil power associated with cold and death. Tezcatlipoca typically carried an obsidian or smoking mirror. His image showed black stripes on his face.

He was a vengeful god who punished bad behavior and evil deeds. The Aztec kings were thought to be his representatives. During their election, they had to stand in front of the image of Tezcatlipoca to perform several ceremonies so their right to rule would become legitimate.

Like most of the Aztec gods, Tezcatlipoca was associated with various aspects of their religion, from the sky to earth, to the north, war, divination, kingship to winds.

Quetzalcoatl

Quetzalcoatl, the Aztec god of winds and rain, self-reflection, and intelligence, was the brother of Tezcatlipoca. His spirit animal was a mixture of rattlesnake and bird, which was also the translation of his name. He was the inventor of books and calendars. According to their myth, Quetzalcoatl infused the bones of the ancient dead with his blood to regenerate humankind.

He was the ruler of the second sun according to the Aztec creation. He was a creator god and the most human loving of the Aztec gods. At the fourth sun’s end, all humanity died. He descended into the underworld and stole all the bones of the dead. He carried the bones to Tamoanchan, a paradise, where a goddess ground all the bones and put them in a jade bowl. Then, he and the other gods shed blood to give the bones new life.

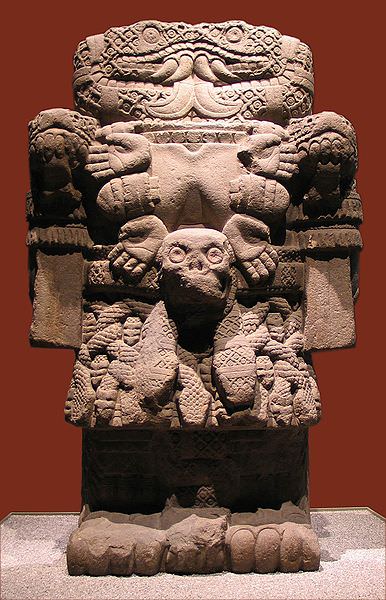

Coatlicue

Coatlicue was the mother of gods and mortals who gave birth to the moon and the stars. Her representation showed a face composed of two fanged serpents. She has a necklace with a skull, hearts, hands, and her skirt has snakes interwoven in it. Many themes were associated to her—agriculture, governance, warfare, childbirth, and earth worship. Legends said a ball of feathers from the sky impregnated her, and she gave birth to the god of war, Huitzilopochtli.

She was the goddess of fertility who predicted that her son would return when the Aztec Empire fell. She was also known as the snake mother, the patron of women who died in childbirth.

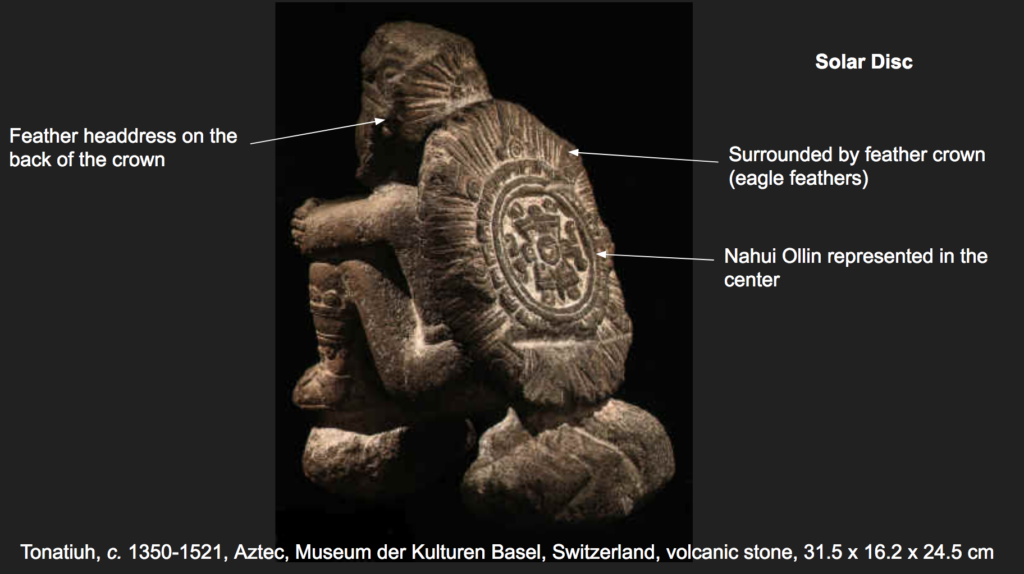

Tonatiuh

Tonatiuh was the sun god, often shown as a symbolic sun disk. He was a nourishing deity who needed sacrificial blood to keep people warm. He was likewise the patron of Aztec warriors. Tonatiuh, linked to ritual sacrifices, required nourishment to defeat darkness daily. In Aztec mythology, he needed heart sacrifices to move across the sky, representing the sun’s movement from day into night. Thus, Aztec warriors often engaged in wars so they could take prisoners of wars (POWs) and offer them as sacrificial victims to Tonatiuh. He was most important to the elite class of Aztec warriors, particularly the jaguar and eagle warrior classes.

His face was the central figure in the famous Aztec sun stone (Aztec stone calendar), now housed at Mexico City’s National Anthropology Museum.

Tlaloc

The Aztec god of rain and storms, Tlaloc, was depicted as a god wearing a mask with long fangs and large round eyes. He provided rain to grow crops, but he was also destructive and unforgiving because he also sent drought and storms. Tlaloc was linked to other meteorological events related to rain, such as snow, ice, lightning, floods, and storms.

Tlaloc was one of the most important deities of the Aztecs as he governed the spheres of agriculture, fertility, and water. He ruled over crop growth and the regular seasonal cycles.

The tears and cries of newborn children were sacred to Tlaloc. Thus, many ceremonies dedicated to him involved children as sacrificial offerings.

Chalchiuhtlicue

Chalchiuhtlicue, the goddess of running water and other aquatic elements, was tied in with serpents. She was often depicted as a deity wearing a blue or green skirt that looked like flowing water. According to Mexica mythology, she played a part in the great deluge (related to Noah and the great flood) that killed most of humankind, but Aztecs believed that she turned people into fish to save them.

She lived in a mountain and ruled over the water that collects on earth, like oceans, lakes, and rivers. The Aztecs believed that the mountains stored water, and she released the water when needed. But sometimes, she withdrew water, leading to droughts. Therefore, the Aztecs offered festivals that involved bloodletting, feasting, fasting, and human sacrifice, including children and women.

Xipe Totec

Xipe Totec was the Aztecs’ god of agricultural fertility. His depiction showed him wearing flayed human skin. For the Aztecs, it symbolized the death of old vegetation and the growth of new ones. According to legend, the symbolism might sound gruesome, but Xipe Totec peeled off his skin to feed people on earth. Like many of the Aztec gods, his festival involved violence and death. Priests removed the skin of the people offered as human sacrifice and wore them for 20 days. Removing the skin from a prisoner symbolized the events that must occur to promote renewed growth during spring, usually related to the growth cycle of maize.

Aztecs were taught not to fear death. People who died by natural causes descended to the underworld four years after death by passing nine levels of tests. However, those who died on the battlefield or in sacrificial offerings would live in paradise.

Centeotl

Centeotl, was the Aztecs’ primary god of maize, typically represented as a young man with a headdress that sprouted maize. A few other deities were associated with the most important crop to the Aztecs. They had Xilonen, the goddess of tamales and sweet corn, Chicomecoatl, the goddess of seed corn, and the god of agriculture and fertility, Xipe Totec.

He was the son of the goddess of fertility and childbirth and had masculine and feminine aspects. According to their language sources, the god of maize was initially born a goddess, only to become a male later. His feminine counterpart was Chicomecoatl, and together, they supervised the different stages of growth and maturation of maize.

Mayahuel

Mayahuel was the goddess of maguey, another important plant to the Aztecs. The Aztecs believed that the sweet sap of the maguey plant was her blood. Furthermore, maguey, a cactus belonging to the agave family, is a principal ingredient in pulque, an alcoholic drink made from the plant’s juice. Thus, Mayahuel is also the goddess of pulque.

Mayahuel was often depicted as having 400 breasts, in reference to the sprouts and leaves of the maguey plant that gives milky white sap (aguamiel or honey water) that people ferment to produce the traditional drink. The maguey plant, known today as the century plant, takes 12 years to mature and has a flower that could grow to about 20 feet high. In order to make pulque, people would cut the flower stalk at the base to allow the sap to collect at the depressed center of the plant.

Tlaltecuhtli

Tlaltechutli was the gigantic earth goddess and the goddess of fertility. Her name translates to the one who gives and eats life. Therefore, she was similar to other Aztec gods and goddesses who needed sustenance from human sacrifices. She represented the earth’s surface that swallows the sun every night but gives it back in the morning.

Based on Aztec mythology, the gods Tezcatlipoca and Quetzalcoatl created the world at the first sun. But Tlaltecuhtli destroyed their creation. The two gods turned into huge serpents and constricted Tlaltecuhtli’s body until her body broke into two pieces. One piece became the earth with its physical features, while the other became the sky. She remained angry, and to compensate for her sacrifice, she demanded human sacrifices often, with people offering human hearts to her.

Mictlantecuhtli

Mictlantecuhtli, the god of death, was one of the rulers of Mictlan, the underworld. He was one of the Aztecs’ principal gods and the most prominent among the other gods and goddesses related to death. His worship activities included ritual cannibalism, with people eating human flesh in his temple. He was a tall god who stood about six feet tall and was described as a skeleton spattered with blood. His head was a skull, but he had eyeballs in his eye sockets. His headdress had paper banners and owl feathers. He wore earspools (earplugs) fashioned from human bones. His necklace consisted of human eyeballs.

In the realm of the Aztecs, the skull imagery symbolized abundance, health, and fertility. Thus, many of the gods had skulls, which, for the Aztecs, represented the close link between life and death.

Xōchiquetzal

Xōchiquetzal, the goddess of women, was in many realms, including the protector of young mothers, female sexual power, beauty, women’s crafts, childbirth, pregnancy, and fertility. She was the mother of Quetzalcoatl. Her name translates to flower precious feather, and she was often depicted as sitting on a bed of marigolds. Her depiction was of a beautiful woman who wore expensive clothing, which was an apt description because she was also the patron goddess of luxury goods manufacturers.

Her entourage consisted of butterflies and birds, and her worshipers usually wore flower and animal masks during her festival, which occurred every eight years. Marigolds were sacred to her, and she was a representative of love spells, magic, weaving, singing, music, and dance.

Mictecacihuatl

Mictecacihuatl, the wife of Mictlantecuhtli, was the goddess of death, and she and her husband ruled Mictlan, the lower recesses of the underworld. Aztecs believed that she went to the underworld because she was sacrificed while still a baby. However, due to the long process of reaching the underworld, she was already a grown woman when she completed her descent and became the consort of the god of death.

Her depiction showed Mictecacihuatl as a corpse devoid of flesh who wore a dress with snakes woven into the fabric. She watched over the bones of the dead in their realm. She also presided over their ancient festivals to honor the dead. During their celebrations for the dead, some of the activities were carried over to the modern-day el Día de los Muertos (Day of the Dead) in Mexico.