The Inca civilization produced some of the ancient Americas’ finest works of art. Incas usually use geometrical shapes for their patterns. The checkerboard was very popular for textiles and pottery, which the artisans produced as tax to the state. The designs varied according to their cultural heritage and specific communities but often showed abstract and geometric representations of birds and animals. Weavers used alpaca, llama wool, and cotton for most of the textiles, reserving the finest wools from young camelids for the garments of the royal family and the nobility.

Potters used natural clay mixed with shells, pulverized rock, sand, and mica to prevent cracking. All pottery was hand-made as there was no potter’s wheel during their time. They used gold, silver, copper, and bronze for metalwork, fashioning them into lime dippers, ceremonial knives, figurines, and jewelry. They also used spondylus shells, polished bone, lapis lazuli, and emeralds as inlays.

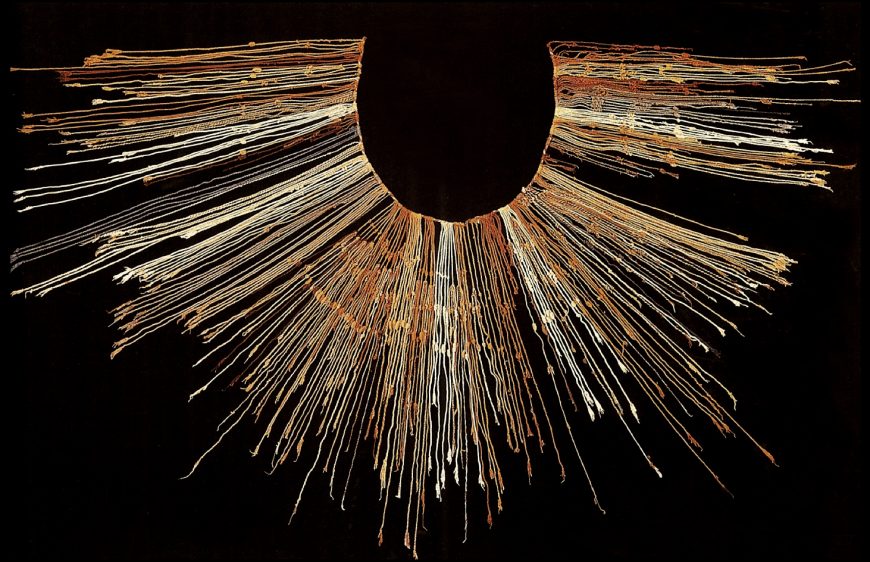

Quipu

The Inca Empire developed a unique messaging system that you can consider an art form. Since there were no wheeled transportation and people often walked on a specific road, they stationed runners at fixed intervals along the way. The runners deliver the messages quickly. The Incas did not have a writing system. What they had was a code system using knotted strings they called quipu. Researchers have not fully unraveled the communication system. For example, some cords have five knots, which researchers assumed represent numbers. However, the knots have specific positions along each cord.

Researchers know that the Incas used the quipu to record important information, histories, livestock herds, harvest yields, population, and tax obligations of citizens. Incas read the quipu from the left looped cord to the loose thinner yarns on the right.

Textiles

The Incas’ textiles were more valuable than precious metals like gold and silver. Chosen women or acllas wove unique fabrics fit for royalty. Many fine textiles they wove became high-status gifts the Sapa Inca (emperor) sent to local lords. They burned some of the fabrics as offering to their sun god, Inti,

The fabrics’ value depended on the weavers’ skills, the dye’s rarity, the spinning’s fineness, and the wool’s quality.

Incas have different fabric types. The coarse Chusi was used for rugs, blankets, and sacks. The Awaska was the standard thick cloth used by the lower classes living in the Andean highlands. Finally, the Qompi was the finest textile the royalty and nobility used. They used the finest wool from young vicuñas and alpacas to make Qompi, which they produced in institutions run by the state.

Urpu

Aside from textiles, the Incas were known for their ceramics. So it is a pity that only a few pieces survived, most of which were found during archeological digs. They produced large jars to store food for the soldiers and officials, such as dried alpaca and corn. They also had large clay pots for brewing corn beer and cooking food.

They used large vessels called urpus to brew asua (corn beer), storage, and food transport. These ceramic vessels were heavy; some were more than four feet high. An urpu has a large handle on each side of the jar and a thick protrusion from the neck’s base. A person or llama can carry the large vase by looping a rope between the handles and over the protrusion. The jar’s pointed base allowed them to push it on the ground so it would remain steady.

Kerus

Incan craftsmen produced different variations of flared beakers they called kerus, used during feasts. They could be made of metal, ceramic, or wood, depending on the drinker’s status. Incas made kerus in pairs, but one is larger than its partner. The higher-ranked person will use the bigger beaker and offers the asua on the smaller cup to the person of lower rank. Drinking together shows their relationship. The nobles had an obligation to provide commoners with food and asua. Likewise, the commoners must provide loyalty and taxes to their rulers. You can see other variations in this list.

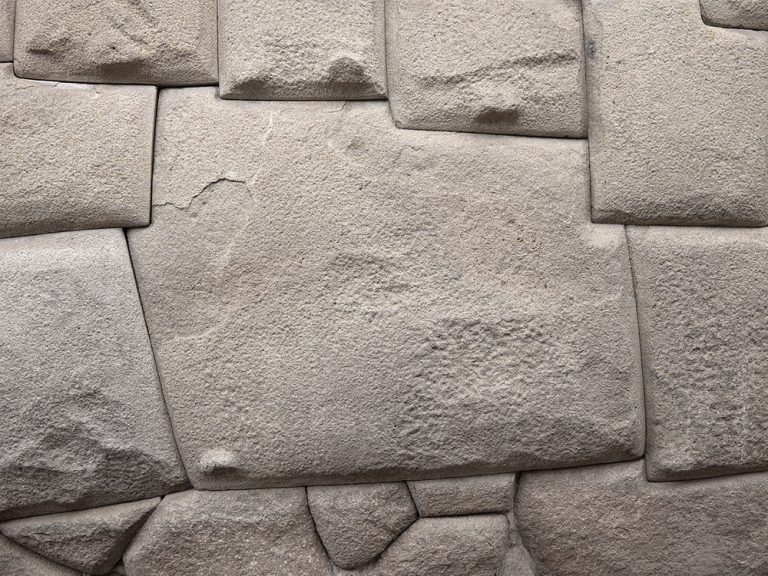

Architecture

Incas were great architects, as evidenced by the buildings they built in conquered areas. Their architectural style is based on stones that fit together uniquely. They do not use stone blocks of uniform size. Instead, they would use stones of varying shapes and sizes and fit them together. It is fascinating that the stones fit closely together, and it is impossible to insert even a thin knife blade between them.

Incan architects shaped the stones with a slight indentation or a slight bulge on the side to lay against each other closely. As a result, the stone blocks can shift when needed, like during earthquakes, but will not separate.

Stone Ritual Vessels

Only a few of these large circular ritual vessels survived. Incas called them cocha, carved from one block of volcanic basalt from Cusco. Researchers think they were used in the Temple of the Sun (Coricancha), probably as a holder of liquid offerings. Some researchers believe they held water to create a reflective and still surface to resemble an eye looking into the underworld. The coils of the snake’s body represent moving water, while ten serpent heads are positioned symmetrically around the vessel’s rim. The arrangement is similar to the ceque system the Incas used to arrange space in Cusco and other areas.

Paccha

The paccha was a ritual watering device that had various imagery and styles. The one shown here incorporated a refined symbolism in its various parts as a ritual device to promote agricultural abundance. It includes a foot plow (taclla), an ear of maize or Zea mays, and a storage (urpu) vessel. When used in the ritual during the start of the planting season, the paccha symbolically represented the whole cycle of maize farming used in the Inca Empire.

Maize on the Cob

When the Spanish came, they found the Qorikancha, one of the most important temples for the Incas. In its courtyard was a garden of people, flowers, corn, and miniature llamas made of silver and gold. One of the most beautiful metal objects in the metal garden was a corncob sculpture in gold and silver alloy. It represented ripe ears of maize breaking through the husk. The maize cobs were still attached to the stalk but ready for harvest. The metalsmiths showed their skill by presenting the individual corn kernels protruding from the cob, expertly combining copper and silver to copy the external and internal parts of the corn. This example is life-sized.

Huascos (Whistling Vessels)

The Incas created whistling bottles or whistling jars, although researchers do not know their exact function. Most of these jars come in human or animal form. Some were plain, while others had more elaborate decorations. Likewise, the size varies. Often, it is a one- or two-chambered vessel with a bird’s head in one of the chambers concealing a whistle. The whistling bottle is globular in shape with flat bottoms and tall spouts. It can make a sound by blowing into the spout. Otherwise, it produces a bird-like sound by pouring liquid from one chamber to the other. Many huascos mimic different animal calls.

All-T’ocapu Tunic

One of the most important artistic expressions of the Incas came from the finely woven fabrics that dedicated weavers produced. The All-T’oqapu Tunic is an exceptional example. It was created during the height of textile production in the Andes.

The tunic used two primary fibers—camelids and cotton. The cotton plants grew along the Andean coast in various natural colors. The camelids include the vicuña and the wild guanacos, alpacas and llamas. The All-T’oqapu Tunic combined camelid wool for the warp (longitudinal threads) and cotton for the weft (horizontal threads), the usual combination for high-quality fabrics.

The tunic’s name came from the square geometric motifs, a design only worn by high-ranking officials in their society. Using the t’oqapu all over the tunic indicates that it was a royal tunic, probably worn by their emperor, symbolizing his power.

Metal Keru

In the Quechua language of the Andes, the term keru referred to wooden cups. Although would was the most common material they used to make the unique beakers, there were silver and gold kerus, although they were rare. There were also keru samples made from ceramic or stone. Even if the Incas put more value on their textiles than precious metals, the materials used for keru also held special meanings.

The golden keru, associated with the bright sun, was reserved for the Inca emperor. Since the Incas worship nature, they associated their ruler with the sun god, while his wife was the moon’s daughter.

Not all sculptors, wood carvers, or metalsmiths can make kerus. The Incas reserved the job for the kerukamayoq. They were privileged specialists who were exempted from farming.

Saywite (Sayhuite) Monolith

The Saywite stone, located in the town of Curahuasi, was made of volcanic rock measuring four meters in diameter and two-and-a-half meters high. Its circumference is 11 meters. The monolith is covered with 300 figures, such as villages with compartments and stairways, animals such as pumas, and plants. There is also sacred geometry reflecting the cosmovision of the Andes tribe. Some researchers say the figures represent maps of the area. Others think the Incas used the rock to experiment with architecture and building designs or to organize irrigation and farming sites. However, the researchers agree that the Incas created the Saywite rock to honor water. The Saywite stone has four sectors corresponding to the direction of the empire.